However much the realm of diary-keeping has been a female experience that has often kept us closeted writers, away from the act of writing as authorship, it has most assuredly been a writing act that intimately connects the art of expressing one’s feeling on the written page with the construction of self and identity, with the effort to be fully self-actualized. This precious powerful sense of writing as a healing place where our souls can speak and unfold has been crucial to women’s development of a counter-hegemonic experience of creativity within patriarchal culture. Significantly, diary writing has not been traditionally seen by literary scholars as subversive autobiography, as a form of authorship that challenges conventional notions about the primacy of confessional writing as mere documentation (for women most often a record of our sorrows). Yet in the many cases where such writing has enhanced our struggle to be self-defining it emerges as a narrative of resistance, as writing that enable us to experience both self-discovery and self-recovery.

bell hooks’s “remembered rapture: the writer at work”

12/28/21: I get a call from the hospital social worker. A wave of strong emotions washes through me. Whereas a younger self would have been left completely undone by this pummel of waves radiating from my emotionally fraught relationship with my father, my spirit feels more sturdy to withstand and accept this present situation. Talking with my brother afterwards, I realize that he has grown a lot, too. The observation that we are both talking openly and candidly about my father, speaks volumes to how transformative this journey continues to be.

What is family? Beyond being a group of individuals who may be tied together by threads of blood, law, choice, and other narratives – perhaps family is in some ways a gift, a mirror, an identity, a home, a wound, a challenge, or an ever-iterative, open-ended dialogue about what it means to love.

12/30/21: My detachment to my father – or rather, to forcing outcomes around his recovery, care, and the status of our relationship – grows. Instead, I find myself turning towards the practice of being present and living fully in the moment with no expectations.

I relinquish my ego and turn to our shared humanity in order to let go of a self-protective clinging unto control and instead, accept reality as it is – to stop denying what is true: the past 2-3 years of my father’s life have been rife with traumatic experiences ranging from a difficult divorce, suffering a stroke and being diagnosed with cancer shortly afterwards, and fighting against housing insecurity as insurance, healthcare, and state agencies have all pressured my father to accept elder poverty and displacement from community as prerequisites for accessing funding for long-term care. My father has both a strong will to live and a strong will to die, and perhaps these dueling drives have existed long before COVID-19 pushed our world into yet another collective reckoning over the soul and future of our shared humanity. And I no longer have any more solutions (defenses?) to appease nor soothe this grief that pools over us all.

Stronger than her will to die was her will to endure, especially when she thought she was being tested. This was the most Korean trait about her, her intense desire to die and survive at the same time, drives that didn’t cancel each other out but stood in confluence…

Cathy Park Hong’s “Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning”

12/31/21: The last day of 2021 is already here. I wake up with a desire to strengthen my body, eat more nourishing foods, and overall grow my health. Restarting a yoga practice has been helping me sleep more peacefully, and I begin having pleasant dreams again. I don’t remember the content, but I feel my mind and spirit growing lighter through the night: a shedding of burdens. I wake up alone without the usual din of urgency. I am simply here and present to face the day.

This morning, I woke up with this lingering realization that I no longer have a strong, reactive desire to escape my life — that is, my familial duties, work expectations, political turmoil, spiritual exile of being a queer woman of color and eldest daughter of immigrants navigating spaces shaped by christian supremacy, heteropatriarchy, U.S. colonialism, and capitalism to name a few totalizing forces. Instead, having built up a store of grounding strategies, resources, and support, I feel more at peace and ready to live in the moment.

Suddenly the words “Can you drink the cup? pierced my heart like the sharp spear of a hunter. I knew at that moment—as with a flash of insight—that taking this question seriously would radically change our lives. It is the question that has the power to crack open a hardened heart and lay bare the tendons of the spiritual life.

“Can you drink the cup? Can you empty it to the dregs? Can you taste all the sorrows and joys? Can you live your life to the full whatever it will bring?” I realized these were our questions.”

Henri Nouwen’s “Can you Drink the Cup?”

I have less of an urge this morning to erase my father completely from my life, to deny the reality of our shared history and connection. And at the same time, I also realized that I can still maintain my boundaries and no longer subject myself to the unpredictable whims of his lashing out and rage. By growing a detachment towards my father and no longer needing him to become someone he is not, I can now navigate how to love my father from a distance and also be honest with myself about the parts of him (and by reflection, me) that I do not love.

Recently, my brother also spoke up to defend me against my father as he had begun another verbal tirade during which he blamed every person, mostly women, in his life for his pain. Looking back, I wonder if this moment is one of the first times my brother acknowledged and actively supported me in my father’s presence.

1/1/22: To sit in discomfort and such intimate quarters with another person’s misery, knowing full well that you cannot (and should not) rescue them from their broken heart nor bottle up their grief unending, or even your own. To let what needs to flow, flow.

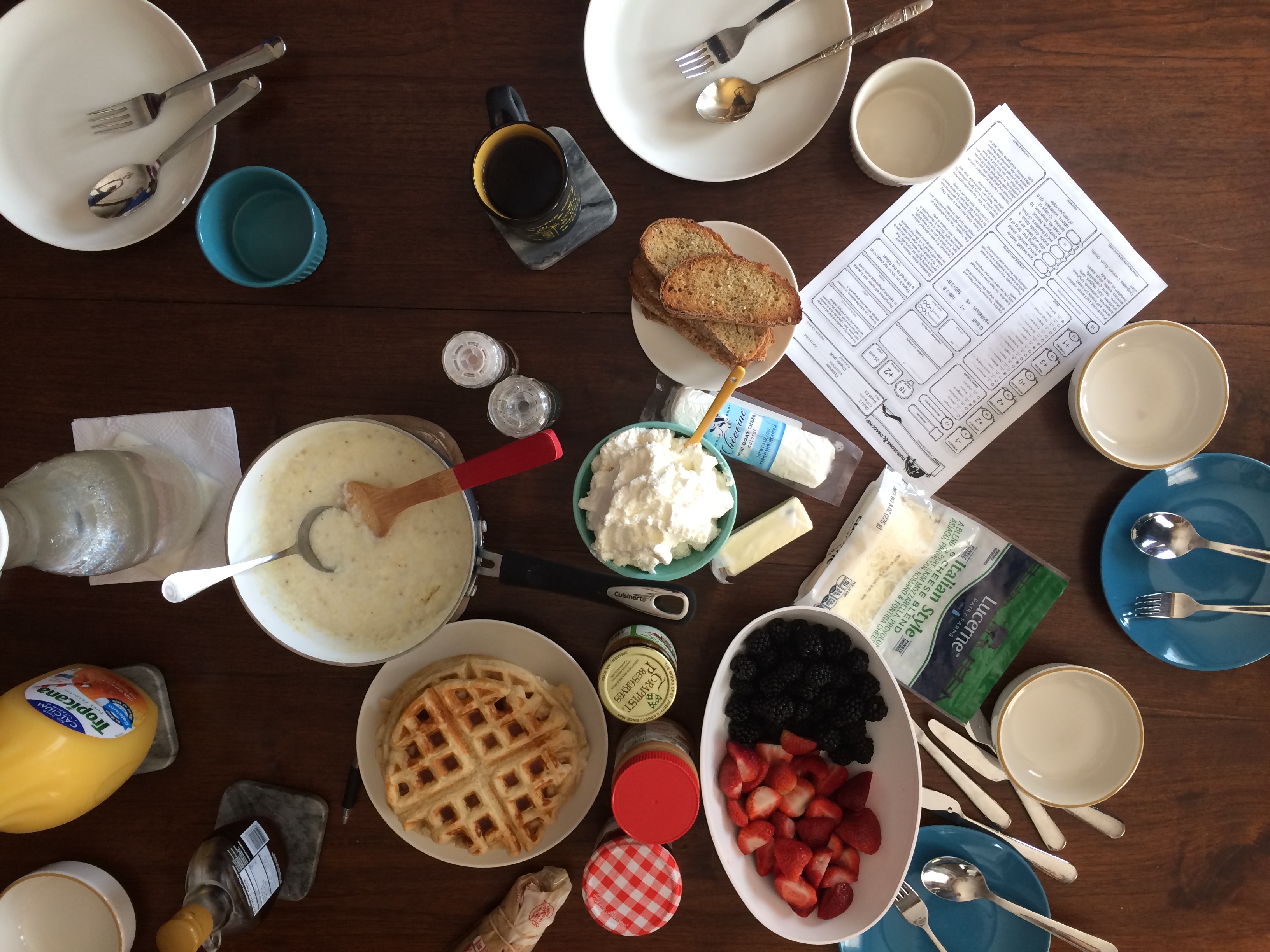

1/3/22: What I did and thought today, a list:

- Finding an assisted living facility that will accept an individual with an active/recent substance use history is challenging. Every conversation with assisted living facilities, hospitals, and social workers can be boiled down to one fundamental task: to clarify what my father is looking for in his coordination of care and housing. For my father, this question remains unanswered.

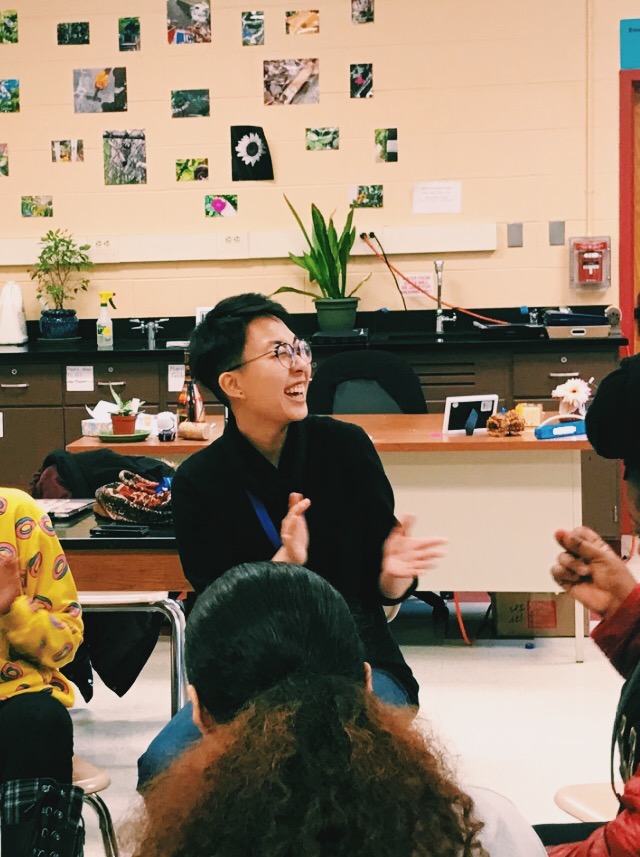

- On forgiveness, letting go, and moving on: How sweet it is to join a weekly yoga/meditation call with Melissa Alexis (Cultural Fabric), and to be welcomed into a space of practice with older women. We are all caregivers in some way, and we are all looking for grounding and cleansing of our energy fields during these difficult times. We can refuse consent to do and hold what the world demands, and we can nurture ourselves to be filled with “light, love, and compassion for all sentient beings.” (Related: Thich Nhat Hanh’s “The First Precept: Reverence for Life”)